What is MAS? Unraveling 2 Critical Meanings in Radiology and Sports: A Comprehensive Guide

Table of Contents

ToggleIntroduction: The Ambiguous Acronym “MAS”

The term “MAS” might appear straightforward at first glance, but its meaning shifts dramatically depending on context. In professional and scientific discussions, this three-letter acronym can refer to two entirely unrelated yet equally important concepts: one rooted in medical imaging, the other central to athletic performance. Without clear context, confusion is almost inevitable. In radiology, MAS stands for milliampere-seconds—a technical setting that governs X-ray exposure. In sports science, it represents maximal aerobic speed, a physiological benchmark for endurance athletes. These two meanings, though spelled the same, operate in completely different realms, serve distinct purposes, and use unique measurement systems. This article aims to clarify the dual identity of MAS, unpacking both definitions with precision, exploring their real-world applications, and highlighting why understanding the difference matters across disciplines.

Understanding MAS in Radiology: Milliampere-seconds (mAs)

In the field of diagnostic radiology, mAs—short for milliampere-seconds—is a foundational exposure parameter that determines the total number of X-ray photons generated during an imaging procedure. It directly influences how much radiation reaches the detector and, in turn, shapes the visual characteristics of the resulting image. More than just a technical setting, mAs is a critical lever that radiographers use to balance image quality with patient safety. By adjusting mAs, they control the overall exposure level, ensuring that images are clear enough for accurate diagnosis while minimizing unnecessary radiation.

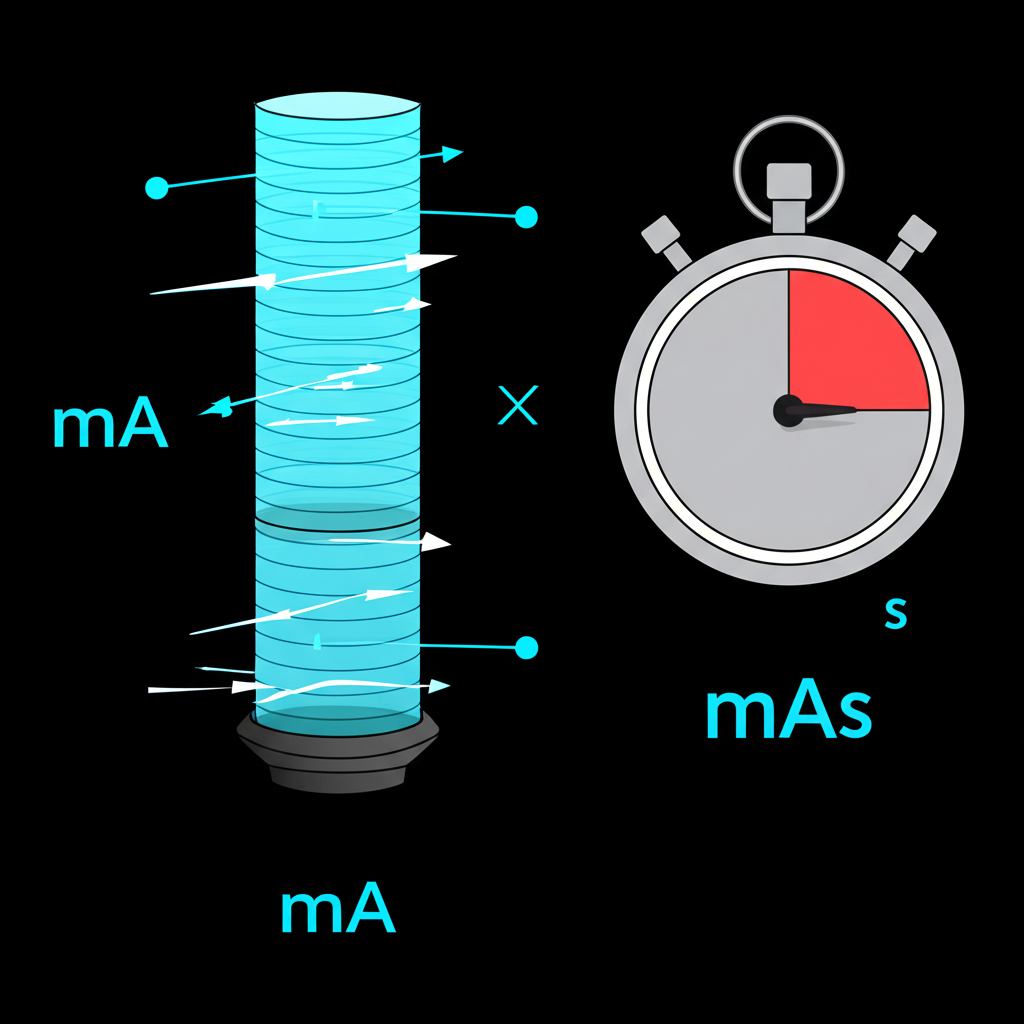

Components of mAs: Milliamperage (mA) and Exposure Time (s)

The value of mAs is derived from two interdependent variables: milliamperage (mA) and exposure time (s). Together, they form a multiplicative relationship expressed as mAs = mA × seconds.

Milliamperage refers to the electrical current flowing through the X-ray tube. A higher mA setting increases the number of electrons released from the cathode, which, when accelerated toward the anode, produce more X-ray photons per second. Think of mA as the intensity of the electron stream.

Exposure time, measured in seconds, dictates how long the X-ray beam is active. Extending the duration allows more photons to be emitted, increasing the total exposure.

For instance, a setting of 150 mA for 0.2 seconds yields 30 mAs—equivalent to 300 mA for 0.1 seconds. This equivalence is clinically significant because it allows radiographers to maintain consistent exposure while adjusting for motion control. A shorter exposure time, even at higher mA, can reduce the risk of motion blur in uncooperative or breathing patients.

The Impact of mAs on Image Quality and Patient Dose

Choosing the right mAs is a balancing act between diagnostic clarity and radiation safety. Its influence extends across multiple aspects of imaging outcomes.

Image density, or brightness in digital systems, is directly proportional to mAs. Increasing mAs results in more photons reaching the detector, producing a darker film image or a brighter digital display. If mAs is too low, the image appears underexposed—grainy and lacking detail. Too high, and the image may become overexposed, losing contrast and diagnostic value.

Patient radiation dose is also linearly related to mAs. Every increase in mAs translates to a corresponding rise in the amount of ionizing radiation absorbed by the patient’s tissues. This is why the ALARA principle (As Low As Reasonably Achievable) is central to radiographic practice. As emphasized by the American College of Radiology, exposure settings must be optimized to deliver the lowest possible dose without compromising diagnostic integrity.

Additionally, mAs plays a key role in managing image noise. Quantum mottle—seen as a grainy or speckled appearance—occurs when insufficient photons contribute to image formation. Higher mAs values reduce this noise by increasing photon flux, resulting in smoother, more diagnostically reliable images, particularly in larger patients or dense anatomical regions.

mAs vs. kVp: A Crucial Distinction

While mAs and kilovoltage peak (kVp) are both essential exposure factors, they affect the X-ray beam in fundamentally different ways. mAs governs the quantity of photons—how many are produced—while kVp determines their quality or energy level.

Higher kVp increases the penetrating power of the X-ray beam, allowing it to pass more easily through dense tissues like bone. This affects image contrast: higher kVp settings produce lower contrast (more shades of gray), while lower kVp enhances contrast, creating sharper distinctions between black and white areas.

A helpful analogy compares the X-ray beam to rainfall. kVp is like the size and force of raindrops—determining how deeply they penetrate a surface. mAs is the duration and intensity of the rainstorm—how many drops fall. Both are necessary to fill a bucket (the image receptor), but they influence different aspects of the outcome. As explored in research on X-ray physics, mastering the interplay between mAs and kVp is essential for producing high-quality, diagnostically useful images.

Calculating and Adjusting mAs in Practice

In clinical settings, mAs is not a fixed value but a variable adjusted based on multiple factors. Radiographers rely on technique charts, anatomical knowledge, and equipment capabilities to determine optimal settings.

For example, a standard chest X-ray may require 10 mAs, achievable through various combinations such as 100 mA for 0.1 seconds or 200 mA for 0.05 seconds. The choice often depends on the need to minimize exposure time and avoid motion artifacts.

The inverse square law also plays a role: when the distance between the X-ray source and the image receptor (SID) increases, the beam intensity drops proportionally to the square of the distance. Doubling the SID requires quadrupling the mAs to maintain the same receptor exposure—a critical consideration in mobile or specialized imaging.

Adjustments are routinely made for:

– **Patient size**: Larger patients require higher mAs to ensure adequate beam penetration.

– **Pathological conditions**: Conditions like pleural effusion or ascites increase tissue density, necessitating higher exposure.

– **Anatomical region**: A lumbar spine exam demands significantly more mAs than a hand X-ray due to greater tissue thickness.

– **Detector sensitivity**: Modern digital receptors vary in speed; faster systems require less mAs to achieve the same image brightness.

Understanding MAS in Sports Science: Maximal Aerobic Speed

In the world of athletic performance, MAS takes on a completely different meaning. Here, it stands for maximal aerobic speed—the minimum running velocity at which an athlete reaches their peak oxygen consumption (VO₂max). It represents the threshold where aerobic metabolism is maximized, and beyond which anaerobic systems must compensate, leading to rapid fatigue. Unlike arbitrary fitness tests, MAS provides a precise, measurable speed that reflects an athlete’s aerobic efficiency and endurance capacity. It’s not just a number; it’s a cornerstone metric used by coaches and sports scientists to design training programs that are both effective and individualized.

The Significance of MAS for Athletes

MAS is more than a physiological curiosity—it’s a powerful predictor of performance, especially in sports that demand sustained or repeated high-intensity efforts. For endurance runners, a higher MAS typically correlates with better race times across distances from 1500 meters to the marathon. For team sport athletes—such as soccer, rugby, or basketball players—MAS reflects their ability to recover between sprints and maintain high work rates over time.

Because MAS integrates both VO₂max and running economy, it offers a more holistic view of aerobic fitness than either metric alone. An athlete with excellent running economy may sustain a higher speed at the same oxygen cost, effectively improving their MAS even without changes in VO₂max. This makes MAS a practical and actionable measure for training progression and performance monitoring.

How to Test and Determine Your MAS

Accurate MAS assessment requires standardized testing protocols that progressively increase exercise intensity until exhaustion. These tests are designed to pinpoint the speed at which aerobic capacity peaks.

One widely used method is the VAM-Eval (Vitesse Aérobie Maximale Évaluation), a shuttle-run test where athletes run back and forth over a 20-meter course, with speed increasing every minute. The final speed completed is recorded as the MAS.

The 30-15 Intermittent Fitness Test (30-15 IFT) is particularly useful for team sports. It involves 30 seconds of running followed by 15 seconds of rest, with speed ramping up every 45 seconds. This mimics the stop-and-go nature of games and provides a realistic estimate of functional aerobic capacity.

Laboratory-based treadmill tests with gas analysis offer the most accurate MAS measurement, directly monitoring oxygen uptake. However, field tests are preferred in many coaching environments due to their practicality and accessibility.

Regardless of the method, consistency in testing conditions—such as surface type, temperature, and athlete fatigue—is essential for reliable and comparable results over time.

Applying MAS in Training Programs

Once an athlete’s MAS is established, it becomes a powerful tool for structuring training with precision. Coaches can prescribe running intensities as percentages of MAS, ensuring that workouts target specific energy systems.

For example:

– **Long intervals at 90–100% MAS** are ideal for improving VO₂max and aerobic power. A typical session might involve 4–5 repetitions of 3–5 minutes at this intensity, with equal rest periods.

– **Short intervals at 100–120% MAS** develop anaerobic capacity and sprint endurance. These sessions often use 20–30 second bursts with brief recovery, challenging the body’s ability to buffer lactate and recover quickly.

– **Tempo runs at 70–85% MAS** enhance aerobic base and lactate threshold, helping athletes sustain moderate efforts for longer durations.

A runner with a MAS of 18 km/h (5 m/s) running at 90% intensity for a 3-minute interval would cover 810 meters—calculated as (0.9 × 5 m/s) × 180 s. This level of specificity allows for highly individualized training, maximizing adaptation and minimizing overtraining.

As supported by research on MAS in sport, training based on MAS leads to measurable improvements in endurance, running economy, and overall performance, particularly in intermittent sports.

MAS in Specific Sports: Running, Rugby, and Beyond

The application of MAS varies by sport, reflecting the unique physical demands of each discipline.

For distance runners, MAS is a direct indicator of competitive potential. Training focuses on increasing MAS through high-intensity intervals and improving the ability to sustain a high percentage of it during races.

In rugby, where players alternate between sprinting, tackling, and jogging, MAS informs the design of high-intensity interval sessions. A player might perform shuttle runs at 105–115% of MAS to simulate game-like efforts and improve recovery between plays. This ensures that conditioning aligns with the metabolic demands of the sport.

The same principles apply to soccer, basketball, field hockey, and triathlon—any sport that combines aerobic endurance with explosive bursts. By tailoring MAS-based drills to sport-specific movement patterns, coaches can enhance both fitness and game readiness.

MAS: A Tale of Two Meanings – Radiology vs. Sports Science

Though they share an acronym, milliampere-seconds in radiology and maximal aerobic speed in sports science are worlds apart in function, application, and measurement. The following comparison highlights their differences:

| Feature | Milliampere-seconds (mAs) in Radiology | Maximal Aerobic Speed (MAS) in Sports Science |

| :————– | :——————————————————————- | :—————————————————————————- |

| **Field** | Diagnostic Medical Imaging (Radiology, Medical Physics) | Exercise Physiology, Coaching, Athletic Training |

| **Definition** | A measure of the quantity of X-ray photons produced, influencing image density and patient dose. | The lowest running speed at which an athlete attains their maximal oxygen uptake (VO₂max). |

| **Purpose** | To control X-ray exposure, optimize image quality, and manage patient radiation dose. | To assess aerobic fitness, predict endurance performance, and prescribe individualized training intensities. |

| **Units** | Milliamperes × seconds (mA·s) | Kilometers per hour (km/h) or meters per second (m/s) |

| **Components** | Milliamperage (mA) and Exposure Time (s) | Determined through progressive running tests, reflecting a physiological threshold. |

| **Impact on** | Image density/brightness, patient radiation dose, image noise. | Aerobic power, endurance capacity, training zones, recovery ability. |

| **Adjusted By** | Radiographers, based on patient size, anatomy, and desired image quality. | Coaches and athletes, based on fitness level and training goals. |

| **Analogy** | The “amount” of light hitting a photographic film. | The “top speed” at which your body can efficiently use oxygen. |

This contrast underscores the importance of context. In one field, MAS is a technical setting on a machine; in another, it’s a personal performance metric. Confusing the two could lead to miscommunication, but understanding both enriches interdisciplinary knowledge.

Conclusion: Mastering the Nuances of MAS

The acronym “MAS” is a striking example of how language in science and medicine can be context-dependent. Whether it’s milliampere-seconds in a radiology suite or maximal aerobic speed on a training field, the meaning of MAS shapes how professionals approach their work. In radiology, mAs is a critical control parameter—fine-tuned to deliver clear images while protecting patient health through the ALARA principle. In sports science, MAS is a dynamic performance indicator—used to unlock an athlete’s potential through data-driven training.

Both uses of MAS, though unrelated, demonstrate the value of precise measurement in optimizing outcomes. For medical professionals, mastering mAs ensures diagnostic accuracy and safety. For coaches and athletes, understanding MAS translates to better training, improved endurance, and enhanced performance. Recognizing the distinction between these two concepts is not just about avoiding confusion—it’s about applying the right knowledge in the right setting to achieve excellence in both healthcare and human performance.

What does the acronym MAS stand for in different scientific and athletic contexts?

In radiology, MAS stands for Milliampere-seconds, referring to an X-ray exposure factor. In sports science, MAS stands for Maximal Aerobic Speed, referring to an athlete’s aerobic fitness level.

How does milliampere-seconds (mAs) directly influence the density or darkness of an X-ray image?

Milliampere-seconds (mAs) directly controls the quantity of X-ray photons produced. A higher mAs value means more photons reach the image receptor, resulting in a darker film image or a brighter digital image. Conversely, lower mAs leads to a lighter/darker (depending on digital display settings) image due to fewer photons.

What are the key factors that determine an individual’s Maximal Aerobic Speed (MAS)?

MAS is primarily determined by an individual’s maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) and their running economy. VO2max reflects the body’s capacity to transport and utilize oxygen, while running economy refers to the oxygen cost of running at a given speed. Genetics, training history, and muscle fiber composition also play roles.

Can an increase in mAs always be compensated by a decrease in kVp to maintain image quality?

No, not always. While both mAs and kVp affect image quality, they influence different aspects. mAs primarily controls image density/brightness, while kVp controls beam penetration and image contrast. Changing one cannot perfectly compensate for the other without altering the inherent characteristics of the image (e.g., contrast or dose), though some reciprocal changes are often made in practice.

What are the most common methods used by coaches to test and establish an athlete’s MAS?

Common methods include:

- The VAM-Eval (Vitesse Aérobie Maximale-Évaluation), a progressive shuttle run test.

- The 30-15 Intermittent Fitness Test (30-15 IFT), which incorporates short work and rest periods.

- Other laboratory tests involving graded exercise protocols on a treadmill.

How does patient size or body habitus influence the required mAs setting in radiography?

Larger or thicker patients (higher body habitus) require a higher mAs setting to ensure adequate penetration of the X-ray beam through the increased tissue volume. This is necessary to achieve sufficient X-ray photon interaction with the image receptor and produce a diagnostic quality image.

What kind of training should I do to improve my Maximal Aerobic Speed?

To improve MAS, focus on high-intensity interval training (HIIT) where you run at or above your current MAS for short durations, followed by recovery periods. Examples include:

- Long intervals (e.g., 4-5 minutes at 90-100% MAS)

- Short intervals (e.g., 15-30 seconds at 100-120% MAS)

- Tempo runs at slightly lower intensities to build aerobic capacity.

Beyond image density, what other aspects of X-ray image quality are affected by mAs?

Besides image density (brightness in digital imaging), mAs significantly affects image noise (quantum mottle). Insufficient mAs leads to a grainy, noisy image, making diagnostic interpretation difficult. Higher mAs reduces quantum mottle, resulting in a smoother, clearer image.

Why is it important for athletes in team sports like rugby to know their MAS?

For team sports like rugby, knowing MAS allows coaches to:

- Individualize training zones for high-intensity efforts.

- Design drills that mimic game demands, improving players’ ability to perform repeated sprints and recover quickly.

- Monitor fitness progression and ensure players are adequately conditioned for the intermittent nature of their sport.

Are there any health risks associated with repeatedly high mAs settings in medical imaging?

Yes, repeatedly high mAs settings mean higher patient radiation doses. While individual diagnostic X-rays are generally safe, cumulative exposure to radiation carries a small, theoretical increased risk of radiation-induced effects, such as cancer. This is why the ALARA (As Low As Reasonably Achievable) principle is strictly followed in medical imaging to minimize patient dose.

You may also like

Calendar

| 一 | 二 | 三 | 四 | 五 | 六 | 日 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | 31 | ||||

發佈留言

很抱歉,必須登入網站才能發佈留言。