Fed Hikes Interest Rate: What 5 Key Impacts Mean for Your Money Today?

Table of Contents

ToggleIntroduction: What Are Fed Interest Rate Hikes?

The Federal Reserve, commonly known as the Fed, stands at the center of the U.S. economic system, wielding substantial influence through its control of monetary policy—particularly interest rates. At the core of this authority is the federal funds rate, which represents the interest rate banks charge each other for overnight loans to meet reserve requirements. When the Fed raises this rate, it sets off a chain reaction across the financial landscape. Higher borrowing costs ripple through consumer loans, mortgages, and business financing, ultimately shaping spending, investment, and inflation. This form of tightening is typically deployed when the economy shows signs of overheating or when inflation climbs above the Fed’s long-term target of 2%. These rate hikes are not made lightly; they are strategic moves designed to balance growth with price stability. In this in-depth exploration, we’ll examine how the Fed makes these decisions, the historical patterns behind its actions, and the real-world consequences for markets, households, and the broader economy.

The Federal Reserve’s Role and How Rate Hikes Are Decided

The Federal Reserve operates under a dual mandate established by Congress: to promote maximum sustainable employment and maintain stable prices. These two goals often pull in opposite directions, making the Fed’s task both delicate and essential. To navigate this challenge, the central bank relies on a range of tools, with adjustments to the federal funds rate being the most visible and impactful.

Policy decisions are made by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), a 12-member group composed of the seven members of the Board of Governors, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and four rotating regional Fed bank presidents. The FOMC meets eight times a year, roughly every six weeks, to evaluate the latest economic data and determine whether monetary policy should be tightened, eased, or held steady.

During these meetings, members analyze key indicators such as the Consumer Price Index (CPI), core Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE), non-farm payrolls, wage growth, GDP trends, and global market developments. Their discussions are grounded in a careful assessment of whether inflation is cooling or accelerating and whether the labor market remains robust or shows early signs of softening. After deliberation, the committee votes on whether to adjust the target range for the federal funds rate.

Once a decision is reached, the Fed uses open market operations—buying or selling U.S. Treasury securities—to influence the supply of bank reserves and guide the effective federal funds rate toward the new target. While rate adjustments are the primary lever, the Fed also employs unconventional tools like quantitative easing (QE) during downturns or quantitative tightening (QT) during recovery phases to manage long-term yields and the size of its balance sheet. Together, these instruments form a coordinated strategy to guide the economy toward its dual objectives.

A Historical Perspective: Major Fed Rate Hike Cycles

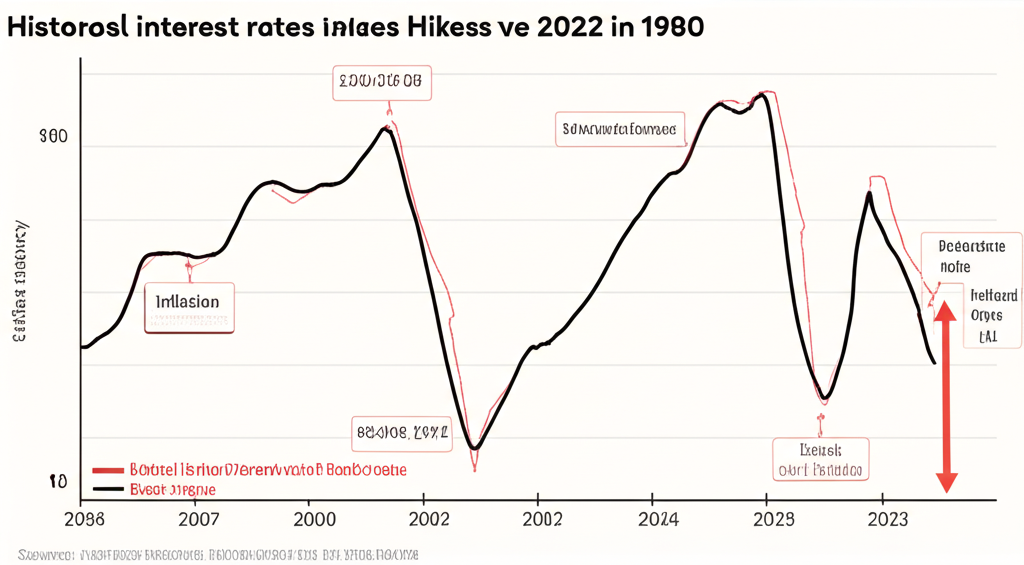

To understand today’s monetary policy, it’s essential to look back at how the Fed has responded to past economic challenges. History reveals that rate hike cycles are often triggered by surging inflation or an overheated economy, and each episode offers insight into the central bank’s evolving approach.

One of the most defining periods occurred in the late 1970s and early 1980s under Chairman Paul Volcker. Facing double-digit inflation driven by oil shocks and entrenched wage-price spirals, the Fed launched an aggressive tightening campaign. The federal funds rate peaked above 20%, leading to a sharp recession but ultimately breaking inflation’s back. Though painful in the short term, this episode established the Fed’s credibility in fighting inflation—a legacy that continues to shape policy today.

In the mid-2000s, the Fed pursued a more gradual path, raising rates from 1% to 5.25% between 2004 and 2006. This cycle aimed to prevent asset bubbles and cool an economy recovering from the dot-com bust and the 9/11 recession. While inflation remained moderate, the tightening contributed to the eventual housing market correction, underscoring the risks of timing and magnitude in monetary policy.

More recently, the post-pandemic era brought a new challenge. After slashing rates to near zero in March 2020 to cushion the economic blow of COVID-19, the Fed faced a surge in inflation by 2021–2022. Supply chain disruptions, fiscal stimulus, and pent-up demand pushed inflation to over 9%—a 40-year high. In response, the Fed initiated one of the fastest and most aggressive hiking cycles in decades, beginning in March 2022. Over the next 14 months, the federal funds rate rose from near zero to a target range of 5.25% to 5.50%, marking the highest level in over two decades. This rapid tightening mirrored the urgency of the moment and highlighted the Fed’s willingness to act decisively when price stability is at risk. Historical data from the Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) clearly illustrates these shifts, offering a valuable reference for analyzing trends in “Fed hikes interest rate history” and understanding the context behind the “Fed hikes interest rate 2022” decision and its aftermath.

Current Fed Interest Rates and Recent Decisions

As of the latest Federal Open Market Committee meeting, the federal funds rate is maintained in a target range of 5.25% to 5.50%. This level has remained unchanged since July 2023, following 11 rate increases over the prior 16 months. The decision to pause reflects the Fed’s growing confidence that inflation is gradually moving toward its 2% target, while also acknowledging signs of slowing economic momentum and a cooling labor market.

In its most recent statement, the FOMC emphasized that future policy adjustments will depend on incoming data, particularly on inflation, employment, and consumer spending. Officials noted that while progress has been made, they remain cautious about declaring victory over inflation. Core PCE, the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, has eased from its peak but still runs above target. At the same time, job growth has moderated, and unemployment has ticked up slightly—a dynamic that increases the risk of overtightening.

The Fed’s communication strategy plays a crucial role in shaping market expectations. Statements released after each meeting, along with the publication of meeting minutes three weeks later, provide insight into the committee’s thinking. Additionally, the “dot plot”—a chart summarizing individual FOMC members’ projections for the federal funds rate—offers a glimpse into the likely path of future policy. As of the last update, the median projection suggests one or two rate cuts could occur in 2025, contingent on sustained disinflation.

For those asking, “What is the Fed interest rate today?” or seeking details on the “Fed interest rate decision today,” the most reliable source is the official Federal Reserve Board website. There, users can access press releases, transcripts, and economic forecasts that provide a comprehensive view of current policy and forward guidance.

The Far-Reaching Impact of Fed Rate Hikes

Federal Reserve rate hikes extend far beyond Wall Street headlines—they reshape everyday financial realities for millions of Americans. The effects are felt across sectors, influencing how businesses invest, how consumers spend, and how investors position their portfolios.

On Inflation and the Broader Economy

The primary objective of raising interest rates is to bring inflation under control. By increasing the cost of borrowing, the Fed aims to reduce both consumer and business spending, thereby easing demand-driven price pressures. When loans become more expensive, companies may delay hiring, capex projects, or expansions. Households may rethink large purchases, from homes to appliances. This cooling effect helps rebalance supply and demand, allowing inflation to recede.

However, the strategy carries risks. If rate hikes are too aggressive or sustained for too long, they can tip the economy into a downturn. The housing market, for example, is highly sensitive to interest rate changes. A sharp rise in mortgage rates can dramatically reduce home sales and construction activity, leading to job losses in related industries. Similarly, higher financing costs can pressure corporate earnings, especially for highly leveraged firms. The goal is a “soft landing”—slowing inflation without triggering a deep recession—but achieving this balance is notoriously difficult.

Impact on Consumers and Borrowing Costs

For individuals, higher interest rates mean more expensive debt. Adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs) often reset higher within months of a Fed hike, increasing monthly payments for homeowners. Even fixed-rate mortgages, while not directly tied to the federal funds rate, tend to rise in response to higher yields on long-term Treasuries, which are influenced by Fed policy. As of 2024, the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate has hovered near 7%, a significant jump from the sub-3% levels seen during the pandemic.

Credit card rates, which are typically pegged to the prime rate (about 3 percentage points above the upper bound of the federal funds rate), have also climbed. Many cardholders now face APRs exceeding 20%, making it harder to manage revolving debt. Auto loans, personal loans, and private student loans have followed a similar trajectory. On the positive side, savers are benefiting. High-yield savings accounts, money market funds, and CDs now offer returns above 4–5%, the best levels in over a decade. This shift rewards conservative investors and provides a buffer against inflation for cash holdings.

Effects on Financial Markets and Investments

Financial markets react swiftly to Fed announcements. Equity investors often view rate hikes with caution, particularly in sectors like technology and growth stocks, where valuations rely heavily on future earnings. Higher discount rates reduce the present value of those distant profits, leading to multiple contractions. Cyclical industries, such as consumer discretionary and industrials, may also underperform as rising rates signal tighter financial conditions.

In contrast, value stocks and dividend-paying companies tend to hold up better during tightening cycles, offering income and perceived stability. The bond market experiences a direct inverse relationship: when interest rates rise, existing bond prices fall because newer bonds offer higher yields. Investors in long-duration bonds have seen notable losses, while those entering the market can lock in higher returns.

Another consequence is the impact on the U.S. dollar. Higher interest rates attract foreign capital seeking better yields, boosting demand for the dollar. A stronger dollar can make U.S. exports more expensive and hurt multinational corporations’ overseas earnings, but it also lowers the cost of imports, which can help ease inflation. Investors often adjust their strategies during rate hike cycles, favoring shorter-duration bonds, floating-rate notes, and defensive sectors to mitigate risk.

Beyond Hikes: Understanding the Full Monetary Policy Cycle

While the spotlight often falls on rate hikes, it’s vital to recognize that monetary policy is cyclical. The Fed doesn’t only tighten—it also eases. After a period of hiking, the central bank may pause to assess the lagged effects of its actions, then eventually pivot to rate cuts when economic conditions warrant.

The shift toward easing typically begins when inflation shows consistent progress toward the 2% target and labor market indicators weaken—such as rising unemployment, slowing wage growth, or declining job openings. For example, during the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic, the Fed slashed rates to near zero and launched large-scale asset purchases to stabilize markets and stimulate growth.

Today, market speculation increasingly centers on when the first rate cut might occur. Phrases like “Will the Fed cut rates in October?” or “What is the Fed rate cut in September 2025?” reflect the anticipation surrounding this potential pivot. However, Fed officials have repeatedly stressed that any decision will be data-dependent. Premature cuts could reignite inflation, while delayed cuts could unnecessarily prolong economic weakness.

Understanding this full cycle—hiking, pausing, holding, and cutting—provides a more complete picture of the Fed’s role. It’s not about maintaining a single direction but responding dynamically to the evolving economic landscape.

Future Outlook: What’s Next for Fed Interest Rates?

The path ahead for interest rates remains uncertain, shaped by a constant flow of economic data. Inflation trends, labor market resilience, and global developments will all play a role in determining the Fed’s next move. While the aggressive hiking phase appears to be over, the timing of rate cuts is still debated.

Market participants closely follow key indicators. The monthly CPI and PCE reports offer insights into inflation’s trajectory. Employment data, including non-farm payrolls and jobless claims, signal the health of the labor market. GDP growth figures help assess overall economic momentum. Even geopolitical events, commodity prices, and housing data can influence the Fed’s calculus.

One of the most widely used tools for tracking market sentiment is the CME FedWatch Tool. By analyzing federal funds futures, it estimates the probability of rate changes at upcoming FOMC meetings. For instance, it might show a 60% chance of no change in June, a 30% chance of a 25-basis-point cut in September, and growing odds of additional cuts by year-end. These probabilities reflect the market’s collective assessment of where policy is headed.

At the same time, the Fed’s own dot plot provides an internal perspective. While individual projections vary, the median outlook suggests a cautious approach to easing, with rate cuts likely to be gradual and data-dependent. Financial institutions and economists publish their own forecasts, but these are frequently revised as new information emerges.

Ultimately, the Fed’s decisions will hinge on whether inflation continues to cool without a sharp rise in unemployment. The goal remains a soft landing—achieving price stability while preserving economic growth. The coming months will be critical in determining whether that outcome is within reach.

Conclusion: Navigating the Fed’s Rate Decisions

Federal Reserve interest rate hikes are a fundamental tool in managing the U.S. economy. Rooted in the Fed’s dual mandate of maximum employment and price stability, these decisions influence everything from inflation and growth to borrowing costs and investment returns. By understanding the FOMC’s decision-making process, the historical context of past cycles, and the wide-ranging effects of rate changes, individuals and businesses can make more informed financial choices.

The impact of the Fed’s actions is not abstract—it touches mortgages, credit cards, savings accounts, and retirement portfolios. Staying informed through reliable sources like the Federal Reserve’s official releases, economic data reports, and tools like the CME FedWatch Tool can help people anticipate shifts and adapt their strategies accordingly. As the economy continues to evolve, the Fed’s role as a stabilizing force remains as important as ever.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About Fed Interest Rates

What is the Federal Funds Rate and why is it important?

The Federal Funds Rate is the target interest rate set by the Federal Reserve for overnight lending between banks. It’s crucial because it serves as a benchmark for many other interest rates in the economy, influencing everything from mortgage rates to business loans and savings account yields.

How does the Federal Reserve decide to hike interest rates?

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meets regularly to assess economic data, particularly inflation and employment figures. If inflation is too high or the economy is overheating, the FOMC may vote to hike rates to slow down demand and stabilize prices.

What are the historical patterns of Fed interest rate hikes?

Historically, Fed rate hikes often occur during periods of high inflation or strong economic growth. Notable cycles include the early 1980s to combat inflation, and the 2022-2023 hikes in response to post-pandemic inflation surges. These patterns illustrate the Fed’s reaction to prevailing economic conditions.

How do current Fed interest rate hikes impact mortgages and consumer loans?

Fed rate hikes typically lead to higher interest rates for mortgages (especially adjustable-rate), credit cards, auto loans, and other consumer borrowing. This increases the cost of borrowing for individuals and can dampen demand for big-ticket items.

What is the effect of Fed rate hikes on the stock market and bond yields?

In the stock market, rate hikes can lead to lower valuations, especially for growth stocks, as future earnings are discounted at a higher rate. In the bond market, existing bond prices tend to fall, and new bond yields rise, making fixed-income investments more attractive relative to equities.

When was the last time the Fed hiked interest rates, and what was the reason?

The exact date of the last hike varies, but the most recent significant hiking cycle began in March 2022. The primary reason was to combat persistently high inflation that had reached multi-decade highs, driven by strong consumer demand and supply chain disruptions.

Will the Fed continue to increase interest rates, or are rate cuts expected soon?

The future path of interest rates depends on economic data. If inflation continues to fall towards the Fed’s 2% target and the labor market shows signs of weakening, the Fed might pause or consider rate cuts. Conversely, if inflation remains stubbornly high, further hikes could be on the table. Market expectations, often tracked via the CME FedWatch Tool, provide insights into these probabilities.

How can individuals track the Fed’s future interest rate decisions?

Individuals can track future decisions by monitoring official announcements from the Federal Reserve Board after FOMC meetings, reviewing economic data (inflation, employment), and using tools like the CME FedWatch Tool, which provides probabilities for future rate changes.

What is the difference between the Federal Funds Rate and other interest rates like the prime rate?

The Federal Funds Rate is a target rate for interbank lending. The prime rate, in contrast, is the interest rate that commercial banks charge their most creditworthy corporate customers. It typically moves in lockstep with the Federal Funds Rate, often set at approximately 3 percentage points above the upper bound of the Federal Funds Rate target range.

How do Fed rate hikes influence inflation and the overall economy?

Fed rate hikes aim to reduce inflation by increasing the cost of borrowing, which in turn slows down economic activity, reduces consumer and business demand, and ultimately puts downward pressure on prices. While effective against inflation, overly aggressive hikes can also slow economic growth and potentially lead to a recession.

You may also like

Calendar

| 一 | 二 | 三 | 四 | 五 | 六 | 日 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | 31 | ||||

發佈留言

很抱歉,必須登入網站才能發佈留言。